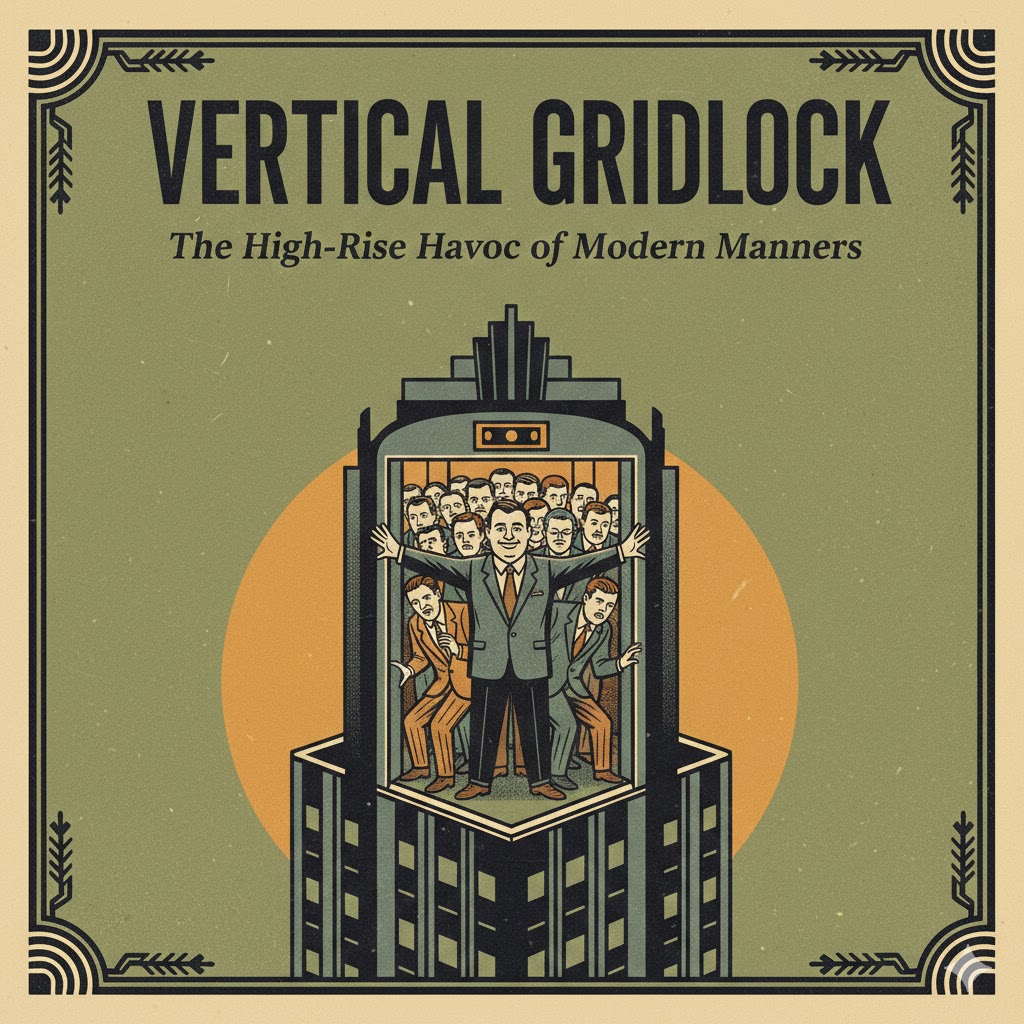

There is a specific, quiet madness that occurs when a group of civilized adults enters a motorized metal box. For the duration of the ascent, we agree to a temporary truce with gravity and a total suspension of eye contact. We are, for ninety seconds, a collection of strangers united by a single goal: reaching the fourteenth floor without an incident. However, this fragile peace is frequently shattered by the pathologically polite – the individual who believes that holding the door is a moral imperative, unaware that they have become a human roadblock in the gears of progress.

We must first address the lobby-level saint. This is the well-meaning soul who spots a fellow human strolling toward the elevator from forty yards away and decides to play the role of the welcoming committee. While the door holder smiles with the smug glow of a local hero, the six people already inside the car are watching their lives evaporate in real-time.

To hold an elevator door for someone who is not already within lunging distance is not an act of charity; it is a temporal heist. You are stealing ten seconds from ten people to save one person from a thirty-second wait for the next car. The math of politeness simply does not track. True etiquette is surgical: if the sensors detect a limb, let it open. Otherwise, let the steel gates of destiny close with the cold finality they deserve.

The most egregious violation, however, occurs upon arrival. We have all encountered The Sentinel – the person standing directly in front of the door who, upon the car reaching its destination, decides to hold the door open for the entire group while remaining firmly rooted in the center of the exit. This is a logistical catastrophe disguised as a courtesy. By holding the door from a stationary position in the middle of the frame, you have effectively turned a wide architectural exit into a narrow, awkward gauntlet. You are not helping us leave; you are forcing us to shimmy past your ribcage in a public display of unwanted physical intimacy.

The correct, intelligent protocol is simple: if you are in the front, you go first. You are the vanguard. Your job is to vanish into the hallway with the speed of a startled gazelle, clearing the path for the masses behind you. If you truly feel the need to assist, just don’t. To stand in the breach is to be the cork in the bottle of efficiency.

No discussion of elevator etiquette would be complete without addressing the Close Door button – that shimmering, metallic lie residing on the control panel. Scientific consensus has long suggested that in most modern buildings, this button is electrically disconnected from the door’s actual motor. It is not a tool; it is a psychological pacifier designed to give the harried professional a false sense of agency. I must confess, I am not above this particular brand of theater. I have stood there, eyes darting to the hallway like a getaway driver, jab-stabbing that button with the frantic energy of someone trying to Morse-code a distress signal. I do this knowing full well that the machine’s internal clock remains entirely indifferent to my tapping. The truly classy move, I’ve realized, is to accept the futility. Now, if I have to press it, I do so with a single, dignified tap – a polite suggestion to the universe – before resigning myself to the machine’s pace. We must all eventually face the fact that while we cannot control the doors, we can at least control the speed of our own social unraveling.

Ultimately, the most sophisticated gift you can give your fellow passengers is the gift of total, dignified invisibility. This silence is sacred. To break it with small talk about the brisk weather is to admit that you cannot handle ninety seconds of your own company. The elevator is not a social club or a stage for performative kindness; it is a transit pipe. The faster we stop being obstacles, the faster we can return to the dignity of not being in a box together.

Leave a comment